| A little bit about

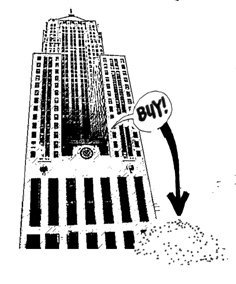

wheat production and futures markets Farmland covers at least three-quarters of Illinois' land area, with nearly 90 percent of farmland categorized as 'prime'. Illinois, the 25th largest state, ranks third nationally in total prime farmland acreage - the state's fertile soil and flat terrain are ideal for farming. Wheat is the third most common grain grown in the state, after corn and soybeans. Acreage devoted to wheat has been declining since the early 1900s, and it now makes up only a small percentage of the state's total land area. Much of the acreage previously devoted to wheat has been replaced by corn and soybeans, which each make up about 30 percent of the state's land. Higher per-acre yields also mean that more wheat can be grown on less land. 2007-2008 was a bumper year for the US wheat crop. Low stocks of grain from the previous season, a strong demand for exports, and the participation of hedge funds in the commodities markets drove up prices to historic levels, reaching $9.70/bushel in March 2009. Sadly, farmers don't always benefit from high prices, having locked in their selling price with a local grain elevator months or even years ahead of time. Elevator operators then sell futures contracts for that same quantity of grain to hedge that price against losses. Grain elevators profit by speculating on the difference between the local cash price and the futures price that occurs at certain times of the year. Futures contracts are contracts to buy or sell a commodity on a given delivery date for a given price. When a contract comes due, rather than taking physical delivery of a commodity the price difference can be settled in cash, resulting in a profit for the buyer or the seller. Most of the transactions on an exchange are for hedging risk or for speculation, and physical delivery on a futures contract is rare. Other than the type of wheat futures traded (soft red winter), the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) has almost no geographic or physical relationship to the wheat grown in Illinois. Still, because farmers, brokers, and grain elevators look to futures prices to determine the cash price per bushel of (real) wheat, the CME is of unmost importance to the Illinois farming community. Recently, the difference between cash and futures prices for wheat have grown larger and more unstable. This creates great difficulties for farmers and elevators trying to manage their risk, and has caused many local grain elevators to go belly-up. Whether or not the wheat market was the victim of excessive speculation was the topic of a recent Senate committee inquiry. The committee found that large purchases of Chicago wheat futures by large index fund traders had driven up prices excessively and "disrupted the normal relationship" between futures and cash markets. Recently, some have made the eminently reasonable argument that rather than being determined by the futures market, cash prices for farm commodities should be determined by the actual cost of production, plus a profit margin - the same way one might price most other products. |

|

|

|

|

||

| [back to Industrial Harvest main page] [ back to background page] | ||